April 2015

by Andy Thigpen

Set is a publication by and for young people dedicated to lifestyle, finance, technology and community. It is published by Leaderhill Credit Union in Muscle Shoals, AL and distributed throughout Middle Tennessee and northern Alabama.

The rain came drizzling down, and the flat sky stretched onward down the highway. We were on our way to Summertown, Tennessee, and we had no clue what to expect.

Our destination was The Farm – an old hippie commune turned cooperative that into living ethically and spiritually in society and nature. For the next three days we met many people, young and old, newcomers and members of the old guard who shaped and continue to shape the identity of the farm. Our job was to figure out exactly what that means.

One thing was for sure: Justin Argo, the photographer has put together a stellar playlist to get our auras burning bright, our chakras aligned and the feet of our souls tapping: Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, Neil Young, Zeppelin (III of course) and the quintessential Grateful Dead.

Every story has a beginning, and ours begins in San Francisco.

The Roots of The Farm

It all started with Monday Night Class. Stephen Gaskin was an English professor / spiritual guru. Every Monday night, he and his students would meet and talk about things ranging from religion to English language to metaphysics. Soon after starting the class, the number of students grew exponentially.

Stephen Gaskin and Jerry Garcia we’re good friends.* (Well… contemporaries anyway – web site editor)

The idea of beginning and intentional community was something that has been mentioned before, but the necessity of starting one wasn’t evident until Gaskin and his caravan went on a nationwide speaking tour. They needed to get out and find a place where they could carry on their beliefs and be dedicated to the Buddhist idea of “Right Livelihood.”

“We sort of threw a dart and came up with Tennessee,” Phil Schwietzer, a member of the original caravan said. They moved to Nashville and spend some time in a park where people used to drive by and look at them. Eventually, due to some happy chances, they found land for $70 an acre and settled right outside of Summertown, Tennessee in 1971 and what was now called The Farm.

“We were immediately the circus,” Peter Schweitzer, Phil’s brother, said. “Nobody knew what the heck we were about, and so a lot of our thing was trying to put people at ease, you know, we’re peaceful, or unarmed, and we’re not that strange. We’re fine with Jesus, which was one of the biggest issues around here.”

The locals, though wary at first, soon grew to respect the hippies on The Farm – due to their bright clothing contrasted with their agrarian lifestyle, they were sometimes called Technicolor Amish.

The Farm began as a commune: Everyone took a vow of poverty and no one owned anything that was his or her own. Any money made or inherited went into the pot, and the food they grew or bought was all rationed out equally. All of them were vegetarians.

It should be mentioned that these people weren’t the free love type of hippies that are romanticized today. While some couples did try group marriages (marriages of two or more couples together) everyone was monogamous. According to Phil, Gaskin had a strict rule: “if you’re sleeping together, you’re engaged. If you’re pregnant, you’re married.”

Also, while smoking marijuana was considered to be a religious sacrament on The Farm, they only ever grew it once – and they got caught. Gaskin was sent to jail for a while and they never grew it again. Everyone I talk to would readily admit to taking LSD more than once in the 60s, but the prevalence of drugs on The Farm seems almost non-existent. These people were here to work, to create a life for themselves and their communal family.

The Farm also had their own rock band.

The communal system they had set up worked reasonably well, but it soon became unmanageable. What started out as a few hundred hippies on The Farm grew to a staggering 1500 permanent residents, plus an extra 10,000 visitors per year.

“What caused The Farm to turn into a co-op as opposed to a commune, more than anything else, was economic,” Phil said. “Had we not had so much difficulty managing that many people with so little cash flow, I think it could have stayed and a communal kind of format.”

After an altercation with Gaskin, the Board of Directors made the decision to transition into a cooperative in 1983. This is colloquially this is known colloquially as “The Changeover.” In the coop system, the land was still own collectively by every member of the farm, but residents now had to pay monthly dues and provide for themselves instead of getting rations from a pile. The whole process was described by some as a “messy divorce.”

Stephen Gaskin, The Farm’s founder, passed away last July.

Eventually however, things settle down. Today, with around 180 residents, The Farm is completely debt free and thriving in its own quiet way.

Part 1: of Hobbitats and Homes

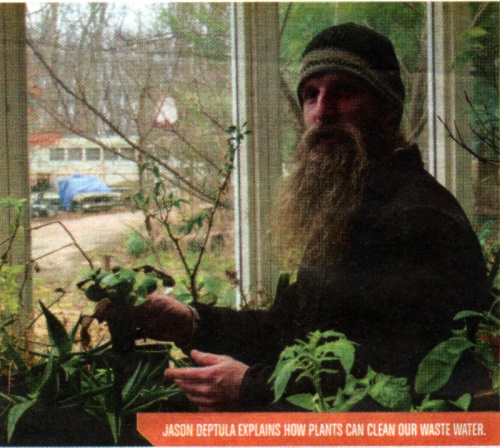

On a rainy day in March, The Farm didn’t seem hospitable. All of the buildings appeared deserted it. There was no movement. A dull brown meadow stretched out to our left as we drove down the paved road. We decided to head down to the Ecovillage Training Center to find Jason Deptula.

We parked in front of a garage with a sign that said “Resourcerer’s Laboratory,” where we saw a few people standing around. Deptula, the Resourcerer, wore a ski cap and a big dirty blonde beard. I shook his hand, which was black from working on an electric golf cart. He is the facilities manager and alternative energy teacher at the Ecovillage Training Center and he, along with some friends and new residents, gave us a tour. I have to say from the beginning that the Ecovillage Training Center was my favorite part of The Farm. Here, they teach people how to adopt a truly green lifestyle by implementing permaculture and natural building. Natural building: “is how to build a house without having to go to Home Depot,” Deptula said.

We parked in front of a garage with a sign that said “Resourcerer’s Laboratory,” where we saw a few people standing around. Deptula, the Resourcerer, wore a ski cap and a big dirty blonde beard. I shook his hand, which was black from working on an electric golf cart. He is the facilities manager and alternative energy teacher at the Ecovillage Training Center and he, along with some friends and new residents, gave us a tour. I have to say from the beginning that the Ecovillage Training Center was my favorite part of The Farm. Here, they teach people how to adopt a truly green lifestyle by implementing permaculture and natural building. Natural building: “is how to build a house without having to go to Home Depot,” Deptula said.

Permaculture is a bit more complicated.

“Permaculture is a design science that you design accordingly that you’re working with nature, not against it,” he said. “So Nature has a way of doing things, and if you understand that and comprehended it, apply and build your stuff around those ways, then you’re working with nature to get the yield you want.”

Permaculture includes things like planting certain plants close to each other for protection or maximum yield. It also includes a system Deptula is working on which will take gray water from sinks and showers and use plants, rocks and earth to clean it before it goes back into the ecosystem.

After hacking some bamboo with a machete (because that’s just what you do,) we continued on.

Deptula introduced us to the “Shout House” – a combination solar powered shower and composting outhouse. Composting outhouse? Yes, slowly, and with time and a bit of wood shavings you too can make a contribution to the earth.

“Its waste, but don’t waste the waste,” Will B. said. Bates is the son of the founder of the Ecovillage Training Centre, who was out of the country.

What had me floored however were the earth roofs. We walked over to a small hut made completely out of clay. “Those are hippytats,” he said. “I’m going to start calling them hobbitats.”

Clay is the most common building material in the world.

Indeed it looks like something Bilbo might live in. It was short and squat with a rocky bass and had a thick layer of earth, moss and grass on the roof. This layer, Deptula explained, is the air conditioner.

“As the plants are breathing, they’re exhaling their evaporating moisture. That’s what air conditioners do,” he said. “So what we have is a natural air conditioning system that requires no input from us except to make sure that the roof doesn’t completely dry out. So the one thing you have to do in a drought is water your roof.”

Part 2: The Farm School

A bit overwhelmed already from the Ecovillage, we set off for the school. As I walked in, a boy rollerbladed toward me. A girl was trying her luck on a skateboard. Others were running through the main hall. Most of them were barefooted, and one of the teachers was too.

Could you expect anything else?

The principal is Peter Kindfield, a man with curly gray hair., day old stubble, & a yin yang earring. From the beginning I can tell that he is deeply invested in his job, and that he has great respect for the children he teaches.

“The focus of the school is sort of two fold: One is that we want everyone to be able to develop their own unique path through life, so we treat every individual has a totally unique individual,” he said. “And that we want everybody to learn how to come together and to create a whole greater than the sum of its parts and be able to put our differences together.”

“We have a very rich curriculum but our primary goal is really helping kids discover who they are and become the best version of themselves that they can,” he added.

“Despite being labeled as a hippie school,” he said, “people are often surprised at how rigorous the curriculum is. When a student transfers out to public school, the student often has a much higher math and science course in the public school students. The Farm Alternative school, and in Kindfield’s ideas, it’s easy to hear remnants of the counterculture. His feelings however, come from years of experience. Kindfield has a PhD and an MA in math, science education and MA in educational psychology, all coming from “Bezerkley” as he calls it. After working with the New York City public school system for a while, he saw exactly how he didn’t want to be to teach.

“My belief is that public education is not only be evolved, but it’s designed to create passive consumers and producers, and we’re trying to battle that as much as possible,” he said. “One of the design features of public school systems is to limit physical activity to get people used to sitting on their asses for 8 hours a day behind the desk, and you know we don’t have that.”

They truly do not. During our conversation standing in the middle of the hall I was rustled and bumped by few rollerblading children, and I almost stepped on another one. “Fridays,” he said “incorporate a lot more physical activity than usual.” What’s interesting is the way that the students and Kindfield address each other. In their tones you can hear that they see each other more or less as equal. Kindfield, I assume, has the ultimate say, but the students don’t cower from him like I remember at school.

“When I came here, I thought, ‘Oh! I’m going to be a curriculum innovator,” and really the best thing I can think of that I did is that my title is principal / janitor. So we don’t have this class thing that principle is this guy in a suit that shakes his finger.

One of the students favorite games they play is called “cops and protesters.” The students of course get to be the cops.

Part 3: Plenty to go around

It’s hard you mention The Farm after my visit and not mention Plenty International. The hippies that came to Summertown on the caravan in 1971 were bent on developing an idealistic community that was sustainable and beneficial to society. But by the time 1974 came they had already learned some skills and needed to move outward.

“We were these idealistic hippies coming out of San Francisco, going to save the world, so what are we going to do besides make our community nice?” Pete, Executive Director of Plenty, said.

They decided it needed to be a non-profit, but they had no clue where it could go. It started small: delivering sweet potatoes and other produce the poor inner city neighborhoods in Nashville and Memphis. It expanded farther to Birmingham, and even all the way to Chicago. Tornadoes came through Alabama, and they came down to offer relief. Basically, anywhere they could be, there they were.

In 1976, a massive earthquake struck Guatemala. At the time, The Farm was using ham radios, so they heard the disaster happen live. They sent a team of builders down there that worked with the Canadian embassy to help rebuild homes and city infrastructure.

Since its inception, Plenty has been involved with projects in over 19 countries ranging from permaculture education to ecotourism to disaster relief.

Anyone can volunteer with Plenty International!* (not quite true – It’s a little more complicated than that – web site editor)

But they’ve also worked at home: from launching a free ambulance service in the South Bronx in the late 70’s, to agricultural development on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. They were in New Orleans just three days after Katrina in 2005, and now they have Kids To The Country which focuses on bringing inner city children out to the country for nature hikes, horseback riding, and to learn skills like teamwork and conflict resolution

“I think one of the most important things for this country is for people to see how other people live in the other parts of the world,” Pete said. “We’re really, really ignorant about our own history, and we really ignorant about world situations, which makes a uncompassionate… I’m all for people traveling – and not just sitting on the beach. Get out and do something. And there’s lots of opportunities to do stuff.”

Part 4: The Future and the End

On Sunday morning, our last morning on The Farm, we had a delicious brunch and one last trip around The Farm.

One thing I was interested in when I got to The farm was what young people thought about The Farm and the future. What will happen to The Farm? What draws people to it and will they want to stay? I caught up with Karuna Kindfield to find out.

Karuna is the child of Peter Kindfield, the principle / janitor and identifies as in a-gender. Karuna prefers the pronouns of they/them/their/theirs and said that their gender identity is a big reason why they love The Farm so much.

“I love it here,” they said. “I’m incredibly grateful that I got to grow up here,. I think it’s really, really a beautiful place, and you know, it fosters the tolerance and environment that I could identify as agendered and people could accept that.”

Duma Davis also likes the non judgemental atmosphere, but she also liked it being a cultural hub.

“I like how this is kind of a hub for people all over the world to come and share their knowledge of things, so you meet a lot of people and hear about a lot of things that you wouldn’t in normal society,” she said.

Trevor Eustace and Laura Look feel the same way.

“Been here 5 months, going on 6. I have no intention of leaving.” Eustis said. “As soon as we got here we fell in love with the place.”

Eustis and Look are from Maine and had set out on a road trip last autumn. The road trip was supposed to last a year, but four days later they ended up at The Farm.

“We wanted a road trip,” Look sad. “But we wanted to find a place that we really felt it home, and that we would imagine ourselves settling down. And we immediately felt that here.”

All of them share a lot of common love for The Farm, and all of them agree on one thing: The Farm needs young people.

“I definitely want more young people,” Davis said. “For a while I felt it was going downhill, but now the 20 and 30 year olds have a lot of ideas for making it more luscious, more gardens and farming and I hope for that.”

“I thought about leaving, but somethings just keeping me down here,” Phorest Cheney, a long time Farm resident, said. “There’s a shortage of young people here. The people who founded The Farm are all getting older, and yeah, you know, all their kids moved away. There isn’t really that much young blood keeping them going, so I think I’m just sticking around to be a young face and somebody doing something.”

As long as more inspired people like Look and Eustis keep coming, it seems that The Farm will last a long time.

“There are people who aren’t going to let it fall apart,” Look sad. “I feel like the younger people are attracting more younger people.”

“Yeah,” Eustis agreed. “This place will keep flowing, I imagine. They will always be calling somebody here one way or another.”

I need to say, what is presented here is barely a scratch on the surface of what The Farm is and what it does. There’s simply not enough space. There’s still the world renowned Midwifery program, SE International which produces radiation detection products and software, the Book Publishing Company, and the Swan Conservation Trust, just to name a few. The amount of work this community has done and continues to do is simply stunning. All I can do is tell you is to go check it out for yourself. Who knows? You may never want to leave.

The Farm’s Farmsoy company makes tofu, soy yogurt and soy milk.