By Tim Ghianni, October 21, 2016

THE FARM – The free and freeing (and sometimes free-wheeling) nature of life on The Farm is perhaps one reason the clumps of flowers have not been removed to make space in Douglas Stevenson’s 50-by-100-foot veggie garden.

“All those flowers are volunteers,” says Douglas, pointing out the zinnias whose bright shots of color punctuate his produce patch.

He envisions a time when he won’t be growing vegetables in this garden, but he has another one not far away. “The trees are getting taller and taking the sun,” he says, adding that another foe of his farming is the common squirrel. “When it’s been so dry, they come in and take the tomatoes.”

Douglas lifts an insect barrier to reveal a healthy stand of romaine lettuce, then adds that a few feet away, the broccoli patch is not quite all right. “The bugs have found their way in.”

Also bearing fruit are the fig trees, but he says he may swap them out in the off-season, as this type of fig ripens too late in the year.

Sweet potatoes are planted in above-ground boxes with bottoms made of hardware cloth (metal screens water can pass through) to keep the moles and voles out, he points out. Across his gravel driveway are his three hives of bees.

Additional Articles in The Ledger: The Vision still lives after 45 Years and Former residents return home.

He steps back to point up at a 50-foot tower, a member of a family of towers – one as high as 100 feet – that bring in the internet. Dishes are located outside most homes to suck TV signals from outer space and into the Tennessee wilderness.

He nods back to the large, two-story cabin he and his family share with another family, friends from early days down on The Farm.

“We both had two kids, all grown now. Both families have separate kitchens and living rooms downstairs,” and there is a central staircase that carries everyone up to a hallway lined with bedrooms and office space.

“We use the same heat-pump and water heater, he says, adding: “Back in the day, 40 people lived here.”

Just two families in his time here, though. “We give each other a lot of space. We have lived together long enough. We don’t need to talk much. We’re pretty mellow.”

The roof, like many in this serene compound, is a heat-reflective white.

“Our summers here in Tennessee are pretty hot,” he adds, noting that heat is sometimes more bothersome than winter’s chill.

Douglas and his wife have left The Farm at times since first arriving in 1973. They have tried satellite camps, “but we wanted to be back here where the action is.”

They also spent two years in Guatemala, where many Farm members go to build homes and bring light to the poverty stricken as part of The Farm’s Plenty program, dedicated to humanitarian, environmental and human rights causes.

For example, while he was in Guatemala with Deborah, their housemates were on Greenpeace’s “Rainbow Warrior” as the ship traveled the seas, fighting for the environment and for threatened species.

While we drive through The Farm grounds, Douglas frequently points to the birthing houses that dot the landscape, evidence of the focus on midwifery that draws many couples from near and far for natural childbirth.

Other pains and illnesses are treated at the clinic. “That’s where they look down your ears, stitch you up,” he explains.

We stop at one recently vacated birthing shelter; a house built three-fourths underground to give it stable year-round temperatures.

It was originally a law office, but that lawyer has moved away.

Was the just-born baby here a boy or a girl? “There’s always somebody having a baby here. I can’t keep up,” he says, adding that his wife is a teacher at the relatively new College of Traditional Midwifery.

Inside this mostly subterranean former lawyer’s office, there is a bed for the mother and a variety of other furniture. Mothers are given the option of using water immersion to help during labor.

“Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world,” reads a part of a quote by Margaret Mead (famed cultural anthropologist in the last century) inscribed below a massive mural depicting The Farm’s history.

It should be pointed out that the father’s duties after birth include the time-honored Farm tradition of “planting the placenta.”

“It is said that one day a person will return to the place where their placenta is buried,” reads a note on thefarmmidwives.org web page.

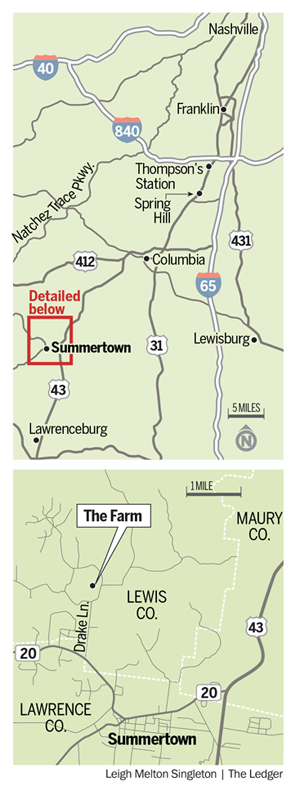

Douglas points out that The Farm is ostensibly in Lewis County. But very nearby are the borders of Maury and Lawrence counties. Borders really don’t mean much out here in the woods.

Douglas points out that The Farm is ostensibly in Lewis County. But very nearby are the borders of Maury and Lawrence counties. Borders really don’t mean much out here in the woods.

Although the focus here is on learning about and fighting for the environment, it was politics that spurred the 80-bus hippie caravan and that also turned other young people on to this utopian experiment.

“At the time, in the ’60s and ’70s, we knew the political revolution was over. Eldridge Cleaver was in exile, Timothy Leary was in jail. Abbie Hoffman had gone underground.” Instead of fighting for political change – the aim of earlier and older hippies – those on the original caravan and other pilgrims “turned toward the land.”

“This is where the revolution is happening,” he says, waving an arm into the distance. “We are allowed to be a model of society off the grid.”

It should be noted that some of these structures weren’t built here. They were moved. The clinic “used to be a church in a nearby town,” adds Douglas, noting that it is just among a number of buildings that were imported.

As a member of the salvage team, Douglas “got pretty good at moving houses.”

That he and the salvage team cart in these homes or even parts of demolished buildings is one of the most striking types of recycling taking place on these acres.

One example: They tore down a warehouse in Columbia and used the “guts” to create an amphitheater next to The Farm Store. That amphitheater has a variety of uses such as concerts and open-air markets on every third Saturday, April -October.

In a nearby gazebo, drumming often takes place, with a bonfire and under the light of the full moon.

Douglas talks about the low point, in 1983, when all of the hippie idealism got snagged in the realities of paying the bills.

Most of the debt came from medical bills at one of the big Nashville hospitals, which then threatened to take a lien on the property, he recounts.

Largely because Farm residents and babies, if necessary, used the emergency room services because they had no health insurance, The Farm was a half-million in the hole.

“We knew that if we didn’t do something, we were going to lose the whole thing,” Douglas says.

The all-for-one, one-for-all ideal just hadn’t worked out, and The Farm had to change its fiscal ways. So the old commune became a collective.

Farm founder, teacher and spiritual guide Stephen Gaskin was no businessman, so he stepped aside – but remained a resident – when a board of directors and a manager took over. Basically, The Farm had a municipal type of government with debt as its first big crisis.

In order to get out of debt, each member needed to go find a job and contribute $100 per month, with $35 more for the debt retirement, which took three years.

Now everyone contributes $105 monthly for the essentials and buys other items from their personal savings.

That meant these hippies had to recant and find outside work. Many went up to Nashville.

Even so, there were great idealists at work here, and the “new” Farm collective pushed, perhaps even harder, to “being a model for sustainable living,” Douglas says.

The change in basic philosophy at The Farm was “about community,” he adds. “You realize you are on a journey. You need to be proactive rather than just wait for things to happen.”

The new collective spent the 1980s quietly rallying from the brink. It now has such services as trash pickup and a Farm bookkeeper. “We also have a swimming area that has lifeguards in the summer. We call it the Swimming Hole,” he says, adding that it is about a half-acre of water.

Still the population shrank to about 100 adults and 150 children during the big changeover.

“By the 1990s, we had to come out of our shells. We still have something to offer somebody. And this is our home.”

He stops to point to the water tower. “Our first water tower was 5,000 gallons and cost us just $1.” The second one holds 25,000 gallons – pretty much what is used daily on this property in the summer. It cost the collective $70,000, just as the paved roadway cost a half-million.

Even so, those who stuck it out insure that hippie idealism survives in the actions of residents. For example, one day last week, The Farm was collecting a trailer-load of wood stoves to send up to the Sioux who are blocking oil pipeline construction through sacred ground.

Standing Rock, site of the standoff, is in North Dakota, so the stoves will be necessary as the seasons change. The Farm also was sending medical supplies.

“We’ve got to support the Native people,” Douglas says. “The energy people have run things long enough.”

Darlene Marks, who was just preparing to begin that trip, adds, “We will stay 4-5 days. The person I’m traveling with is a carpenter.” He can help with construction of stable shelter for the Native people.

“What you put out comes back to you,” she says. “This is our second run.”

Douglas leads the way to what was the original “downtown” Farm settlement back in 1971. “That one house (it still stands, though it is cloaked in overgrown shrubbery) was the only one here. It also had the only flush toilet and the only shower.”

Those who couldn’t fit into that house camped out, slept in buses and began to build their own places. Nearby is a small shed, the Post Office, Douglas notes, as cars begin arriving from around The Farm for people to pick up their bills, political fliers and other U.S. Mail.

“See that other little shed? That’s firefighting equipment,” Douglas explains. “We use that when we have an all-points.”

Everyone knows to come, use rakes and things like that to put out the brush fires (the most common fire).”

A county volunteer fire department is just up the road from The Farm entrance, and they can be called if there is a bigger catastrophe, just as county deputies can be called if needed in the event of crime. The latter hasn’t been much of a problem, though, Douglas says, noting “everybody knows everybody.”

He stops the tour long enough to go talk with a woman in a van, traveling toward the gate. It’s his daughter, who is an accountant at the flourishing Geiger counter factory.

“After Three-Mile Island, after Chernobyl, after Fukushima, these have been real popular,” he says, allowing that the radiation detectors are sold worldwide.

Pilgrims have continued to arrive regularly. One, Jason Deptula (“The Resorcerer,” whose shop is at the Ecovillage Training Center and who pretty much takes care of whatever requires skilled hands for repair) is working on a string of LED lights to wrap around an oversized golf cart used to give tours.

“We have all kinds of colorful lights,” he says, eyes flashing with good humor.

Deptula and his wife have been on the collective for 13 years. “We came here pregnant. The midwives caught our baby,” he adds.

“Resorcerer’s Laboratory” (essentially a garage) is where the Farm prepares and repairs its missions.

Hayley Smith is the Ecovillage Training Center’s program director. Laura Look is the hospitality manager (making sure those who are coming here have beds in the EcoHostel and elsewhere.) Many folks choose abandoned buses “parked” in the woods. One of the buses even participated in the 1971 caravan.

Smith runs a variety of ecology-slanted education programs for visitors, “but we contribute to whatever we have to.

“I also can clean toilets,” says the young scientist and sustainability educator.

Look came here about two years ago when she was “looking for America” on a road adventure with her partner. They made it no farther than The Farm.

“I found The Farm on accident,” says the 24-year-old. “We stayed.”

Smith, 33, a former geosciences and watershed-science educator in North Carolina, arrived one year ago. “I was dissatisfied with a 9-5 job, but particularly (dissatisfied) in academia, where we TALKED a lot about sustainability. Here is where they are actually trying to put those principles in practice,” she says.

“I came here and it was a good fit. I knew there was a way to show people the best way to do things.

“Some come here to learn about sustainability. Others come for the spiritual experience,” Smith notes, bending over to pet the head of her dog, Seala, an 8-year-old rescue hound.

Dogs in general are forbidden from the Ecovillage, primarily because chickens wander freely. “I told them that if they wanted me, Seala was coming with me.”

She and Seala lead Eco lives. A solar panel is indeed a water heater. The shower she uses is an open-air facility, with modesty protected by wooden walls. All “gray water” (from showers and sinks, etc.) is collected in a pond, waiting to be reused.

She adds that when people stay here they “contribute” to the environment by using compost toilets. The waste is brought out and for three or four years is spread out in the bamboo grove and elsewhere. And then it can be used as nutrient for anything but the food plants.

“Our excess is full of nutrients,” she says. “It’s an opportunity to show the nitrogen cycle.”

Like a stoic schoolteacher, she explains that cycle: Plants are eaten by animals, and humans eat both, “and the excrement is filled with valuable nitrogen for the soil.”

The Green Dragon building is the heart of the center and is used to give lessons in sustainability to adults and to young people. Schoolkids – including many brought from inner-city Nashville as part of the Kids to the Country project – have made much of the structure from natural plaster and reused bottles.

Kids to the Country is “the baby” of Mary Ellen Bowen, who came to The Farm in 1976, a single mother with three children, seeking a future for her kids unlike the life she had growing up in Chicago.

Her program brings these underprivileged urban children to The Farm for weeklong programs during the summer. They not only enjoy the outdoors – something they can’t do safely in public housing or other rough spots beneath the fabled Nashville Skyline – but they also learn mediation and conflict resolution.

“I offer inspirational, transformational experiences” to these campers, Bowen says, adding that there are times when members of The Farm come to Nashville to work with these at-risk kids.

“Make sure you say we need sponsors,” she says. “It costs $350 a week,” and pays off by bringing a sense of the world to the kids.

Smith has little time to rest as she battles for sustainability education. “Now there’s always work in progress,” she says, taking a few steps to the Fairy House, where she lives with Seala. “It was already begun when I got here.” She completed it by using homemade plaster and paints and stone for the floor.

Seala and Smith last winter “found out what it’s like to wake up at 2 in the morning, open up the stove to see if there were still coals, then add wood.”

The EcoHostel itself, by the way, is even on Airbnb. “It is pointed out on Airbnb that this isn’t your normal Airbnb. It is a way to come have an experience,” Smith says.

Smith adds she has hopes that more visitors will come here for the experience. And she wants to entice more people to have meetings out here, learn about the nitrogen cycle.

She grabs a stick to knock a fresh pear from one of the trees. “You can rinse it off, but they say all the microbes that are on it when you pick it off the tree are good for you.”

The unwashed pear is crisp and juicy.