On The Farm with the Flower Children’s Children

by Ingrid Groller, Parents Magazine, July 1979

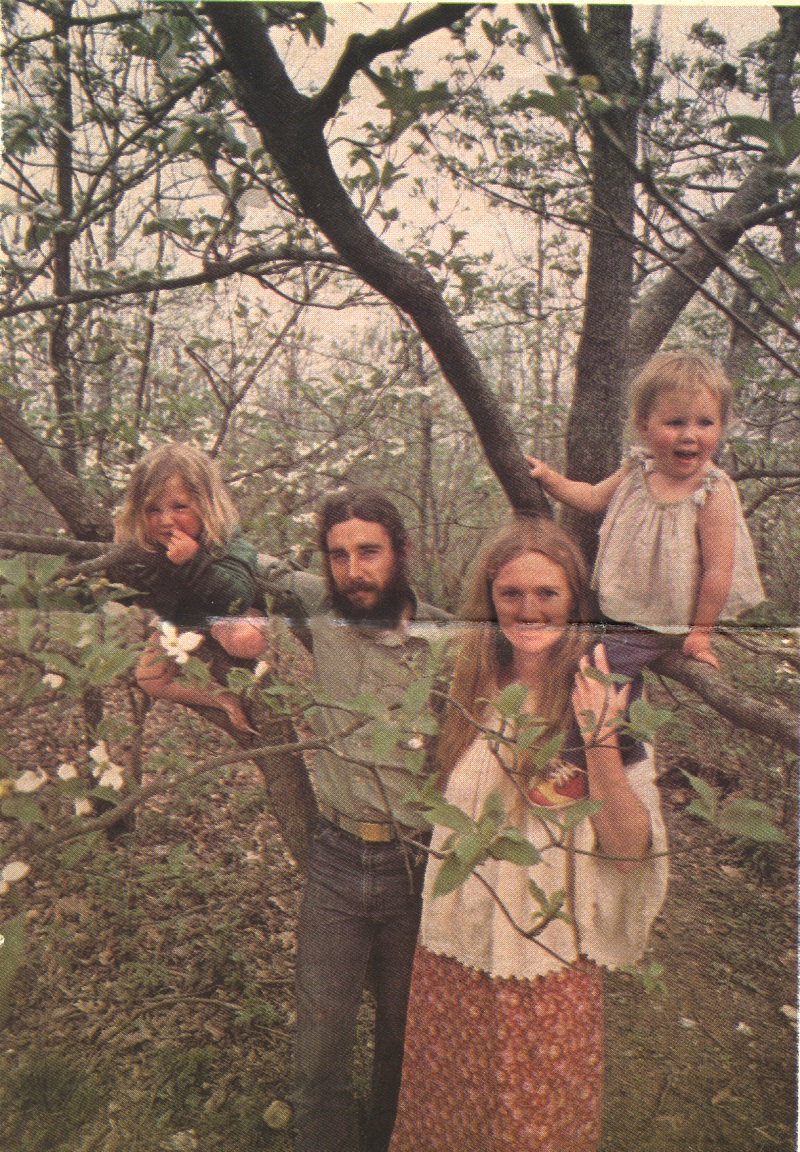

Back in the hills of southern Tennessee, among the Dogwood and the tall oak trees, a group of 60s San Francisco flower children have established a community called The Farm, where children have a status not found in the rest of our society. The Farm’s spiritual leader is Stephen Gaskin, a lay preacher committed to practicing an ideal of nurturance and brotherhood.

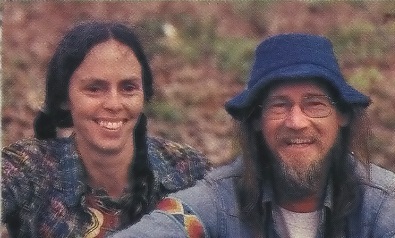

Ina May Gaskin, the community’s head midwife, with her husband Stephen Gaskin, the community’s spiritual leader.

The Farm was established in 1971 when Stephen and 270 of his friends arrived in Tennessee where they had heard land was cheap. It was: the group pooled their money and bought 1014 acres of land at $70 an acre. Since then, another 750 acres have been purchased at $100 an acre. The population, which fluctuates (members are free to come and go as they please) has grown to over 1000, 489 of them children.

By living simply and collectively, The Farm’s inhabitants are striving to be self sufficient. The Tribal Council of about 25 make decisions regarding what is referred to as the community’s material plane. There’s no pay for work, no charge for any goods or services, and no amount of work required. Most of the food is grown and processed on The Farm. Items bought in town such as cooking oil, toilet paper, dishwashing liquid, etc. – are distributed through The Farm Store. Construction crews, a book publishing company, and a food company make money for the community. There’s a school, a health care facility, and an ambulance service that also serves The Farm’s neighbors and carries anyone seriously ill or injured to a nearby hospital. Midwives provide services not only for The Farm, but for nonmember couples and single women who choose to deliver there.

Preparing Dinner: Denise Lichtman and her sons, Benjamin, 7 1/2, and Joseph, 4, pick kale for dinner.

The Farm’s members are vegetarians (they don’t even eat dairy products) and depend heavily on soybeans for food (Some 250 acres a year are planted.). Nonviolent, they won’t even kill rattlesnakes found on their land.

At first glance The Farm might not look like much. The bumpy, dirt road runs from the gate past the community’s bakery, soy dairy, and wood shop, housed in buildings made from salvaged lumber. Homes sit among the trees on the dusty dirt roads that lead off the main road. The Farm’s population is spread out among approximately 50 separate households, ranging in size from a single-family to 40 people. Like the business buildings, the homes are made from much recycled material. Each house has an outhouse, but they also have running water, showers, heat from wood burning stoves, and electricity.

Newcomers: Juan Salvajan and Myra, a 13 year old with a crippling bone disease, recently came to Tennessee from Guatemala.

In all Farm households, everyone shares the kitchen, main living area, bathroom, and out house. Couples have their own bedrooms; single people share rooms. Depending on the household, all of the children from one family share a bedroom, or there is a girl’s room and a boy’s room shared by the kids from all the families in the household.

Many of the households on The Farm have their own birthing rooms overseen by the lay midwives who provide prenatal care and officiate at all births on The Farm. The midwives were trained by Stephen’s wife, Ina May, who shares with him an easy smile, dancing eyes, and compassionate sense of humor. “In my mother’s day, it was accepted that having a baby was a horrible experience,” say Ina May, who, with Stephen, has five children. “But the word is getting out now that it’s not just OK – it can be fun.”

Ina May never had any formal nursing or medical training, but she has had the support of a local doctor, affectionately refer to as “Dr. Feelgood.”

The Farm trained midwives, whom Ina May describes as “people you’d like to see when you’re feeling vulnerable,” are proud of their birthing statistics. They have been only 15 perinatal mortality among The Farm’s 1015 births – significantly below the rate in Tennessee as a whole. And while hospitals often have a 15% cesarean rate, Farm midwives and the two physician Farm members who help deal with emergencies have had to send only 15 women to the local hospital for cesarean deliveries.

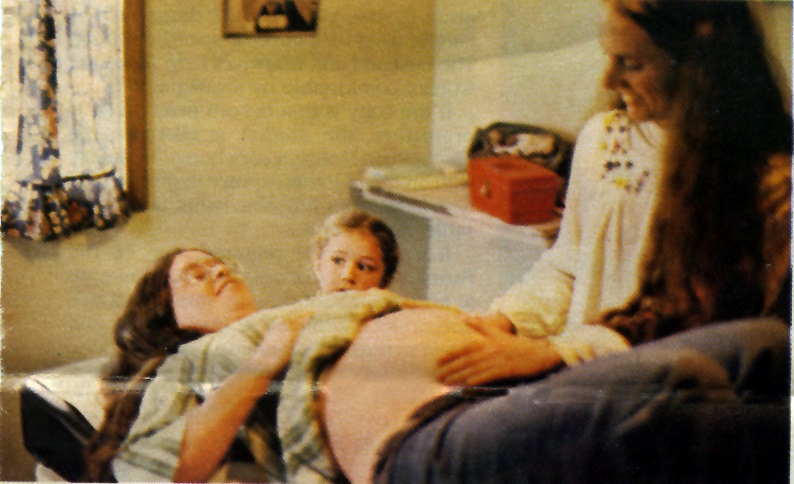

Prenatal Checkup: Cara O’Gorman, a Farm midwife, examines Cynthia Bates, who’s seven months pregnant, while Cynthia’s daughter, Gretchen, 5, watches.

Ina May smiles when she says their success is due to the fact that “we never charge money,” but their statistics are as much a reflection of The Farm’s prenatal care program. Pregnant women are examined by midwives once a month for the first seven and a half months, then once a week until they go into labor. No special childbirth classes are given, though, as the prevailing Farm wisdom is that what you need to know, you can learn on the spot. When labor starts, midwives are summoned into the household. For the most part they just let nature take its course. No anesthetics are given to ease pain, nor are drugs such as Pitocin used to induce or speed up labor. The husband and midwives make the woman comfortable by massaging her.

If the baby is in a breech position or is premature, the mother is taken to the Tower Road House, a cozy home like facility with an infant intensive-care unit equipped with incubators, bilirubin lights and a portable oxygen unit. If a cesarean is required, one of The Farm’s two ambulances takes the mother to a hospital about 15 minutes away where she is admitted as an outpatient and given a spinal anesthetic so she can be conscious for the delivery; she and the baby are released that day to recuperate on The Farm.

Under the Lights: Dr. Jeffery Herganrather, mother Rita Sherman, and brother Harry, 3, check on Sarah Sue, three days old here. A premature baby with a mild case of jaundice, she had to spend a week in the incubator.

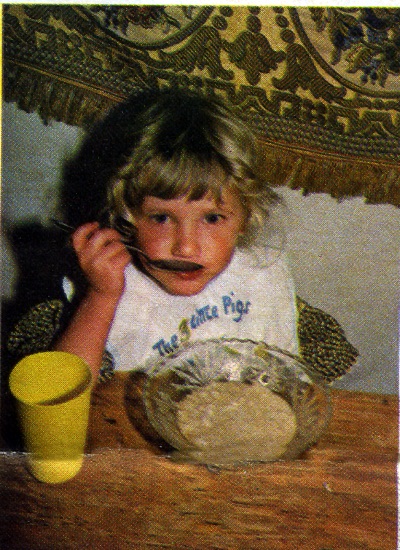

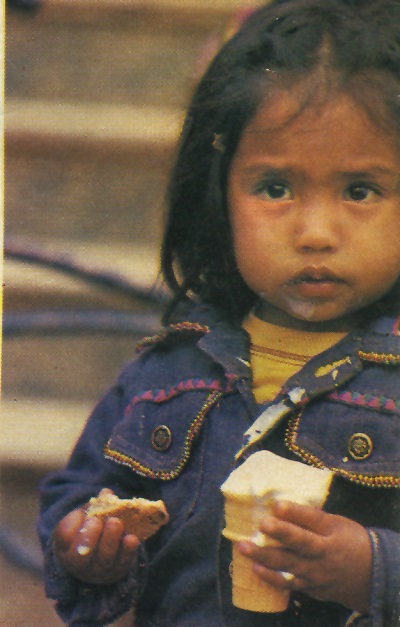

Javier enjoys a soy ice cream cone. Abandoned in Guatemala, he was adopted by Marjorie and Michael Knott.

While just about anyone outside of the community is welcome to have her baby at The Farm, a special offer has been extended to single women. The Farm Midwives state, “If you or anyone you know is thinking about getting an abortion, here is an alternative: we will deliver your baby by natural childbirth for free. If you decide to keep the baby, you can; or we will raise it for you. If you ever decide that you want the baby back, you can have it.”

Many of the single women who have accepted that offer have ended up staying on The Farm and raising their children there. Only six children have been left there so far.

A unique feature of The Farm certainly is that there is such harmony with so many children. Farm parents make an effort to raise their children to be friends, not underlings, and Stephen cautions parents not to “start on a track that’s going to alienate you from your kids.” Children who are misbehaving (not cooperating, not wanting their turn, etc.) are told, “Be nice.”

Those who do get out of hand are removed from the center of activity by a parent and talked to quietly until they calm down.

Although babysitting responsibilities are shared in the households, children are raised by their own parents. To keep the family unit solid, families make it a point to spend some time alone together each day. After having dinner and maybe watching a television program or two with the group, they go to their own rooms for an hour or two together. (Television viewing was more restricted originally than it is now, but children still watch under adult supervision. When commercials come on the sound is turned off and it’s an honor for a child to perform that chore.)

During the day, the younger children are at home, being cared for by the “House ladies” in charge that day. Or they may be out with their parents who are going about their daily business.

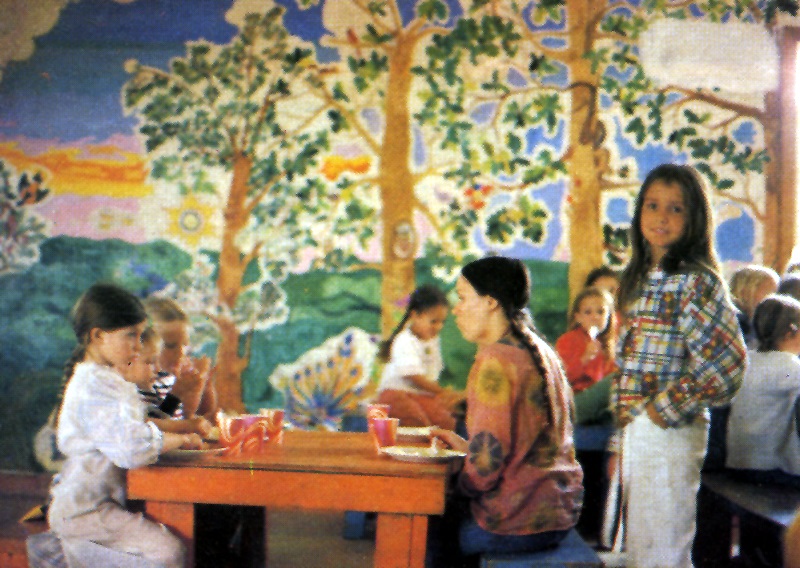

School lunch: Above, schoolchildren, along with some of their parents, enjoy a lunch of macaroni and cheese (made with Nutritional Yeast), coleslaw, and lemonade from the school cafeteria. Dessert was soy ice cream. Because of space problems, classes meet for only half a day. But all the kids eat in the school cafeteria, which they say is run by the best cook on The Farm. Kids will even come early to help out with lunch.

School-age children (there are 210 of them) attend The Farm School, which follows much the same curriculum as do public schools across the country. In addition, vocational training is offered beginning in the 9th grade, allowing students to work as apprentices in The Farm’s industries and businesses during the half day they’re not in school.

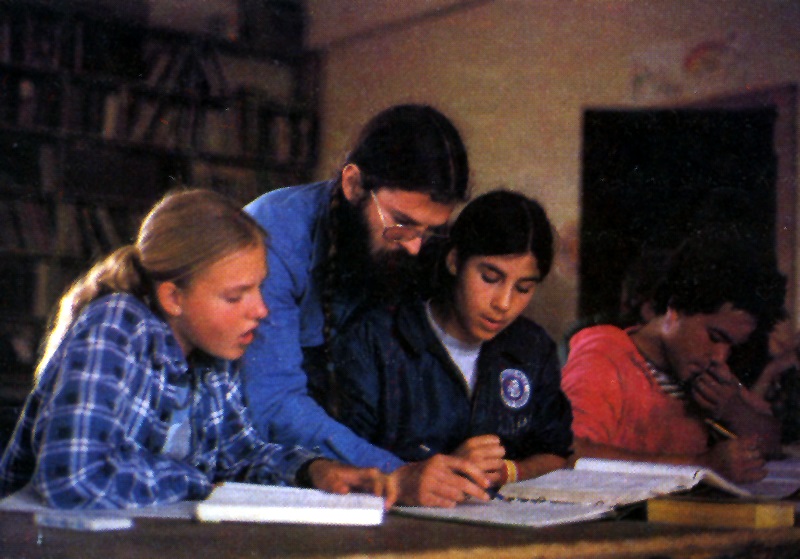

Individual Attention: Farm Classes have a high student-teacher ratio. Here, Richard McKinney, a teacher’s aid, works with ninth and tenth grade math students.

“School is much more fun here,” says Beth Lloyd, 33, head teacher for the 11th and 12th grade. Marilyn Keating, the head of the school, adds that the structure is looser, students and teachers on a first name basis, and there is a higher teacher-student ratio, since other adults come in to help out in the classes. During a 9th and 10th grade math class – in which students worked on algebra, geometry, and general math, depending on ability and interest – there was a teacher’s aide for every two or three students.

Cafeteria Art: Two murals, done by the kids, decorate the school cafeteria. One is shown here. The other is The Farm’s tractor trailer.

The Farm School also makes a point of upholding the community’s values. Teachers talk to the children about being nice and taking care of one another. Farm history is taught too.

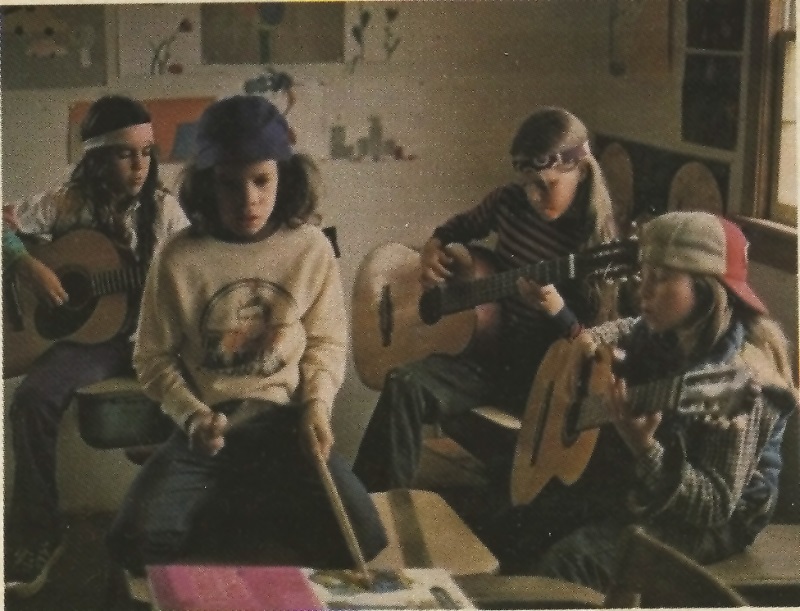

Rolling Thunder, one of The Farm’s young rock groups, performs during a fifth and sixth grade music class. Everyone joins in – either on guitars, with rhythm sticks, or by singing. The kids do everything from a Spanish version of “Twist and Shout,” to songs they write themselves.

Beyond the school, the strong moral values of the community shape the child rearing on The Farm. The children are “part two” of The Farms dream, Stephen says. But he adds “It remains to be seen whether we all stay here, or at some point scatter and flee. If we do stay here, do the kids stay here and does it go on to the next generation?”

Ina May Gaskin, head midwife, teaches a Chinese class to seventh and eighth graders. Earlier in the year they studied Spanish.

Beth comments that, “ There’s a heavy urge at that age to go and see the world. But we hope that we’ve made it nice and sane enough for them here that they will stay.”

Protests have already been heard from the kids. Disagreeing with their parents on the TV issue, they wrote this song (played with guitars to a heavy rock beat):

One time we were watching TV,

and someone said it rots your mind.

But you’ve got to watch the media,

or you’ll be left behind.

It was a protest alright, but one that stems from the attitudes learn from their parents. It looks as though even if these children grow up and go elsewhere, they will be taking The Farm’s values with them.