The Farm – The friendliest place in America

by Jill Johnston, The Village Voice, Jan 3, 1977

Freak America is not over – It’s just become serious and functional.

If you have in your mind’s eye long enough an image of what you want for something it’s bound to come true. This particular image I’ve had in my mind for quite a while was a place where my kids could go and hang out constructively.

I wanted them to go to some school of life, a place where you can learn a bunch of things and learn how to be with lots of people. However I didn’t want to send them there, wherever there was. I just wanted them to somehow migrate there of their own apparent accord. I don’t believe in sending people places, and I’ve regarded my kids as people since they were six and seven respectively. I’m not going to tell the story here of why I didn’t see them as people before they were six and seven, but as soon as I saw them as people I refused to have anything to do with sending them to the public schools.

I had also given up on the idea of some special sort of school. I didn’t believe one existed. You’d have to start one yourself. That’s what people have always done. And I had my own school of-life correspondence course in operation. Basically you want to be your children’s friend and it isn’t friend to send somebody you care about to any mean places.

Eventually maybe the world will be a friendly place and we won’t have to worry about these things. In the meantime, if you keep projecting images of friendly places in your mind’s eye, and you’re reasonably friendly with your kids in other words they pretty much share your attitudes, they’re bound to migrate of their own accord to the right friendly places.

This is frankly my only criterion for going places – these days, although if a place doesn’t feel friendly when I get there I’m willing to try and hassle things out until it does. From this preamble anybody should be able to see how natural it would be for two adults like my teenage children to migrate eventually to Stephen Gaskin’s Farm in Tennessee, which may be the friendliest place in America. Winnie heard about the Farm when she was living on the coast last year. She says she also knew about Stephen from seeing one of his books on my bookcase. I knew about The Farm at least three years ago (it’s five years old now, but I didn’t take it seriously because I was strung out between two revolutions.

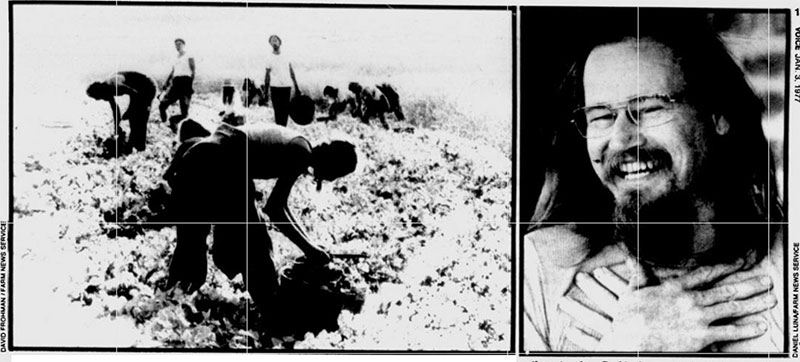

A thousand people live on the Tennessee farm, whose largest enterprise is food production. Former college teacher Gaskin is now a “kind of pastor.”

I actually saw Stephen speak in San Francisco at The Family Dog auditorium in 1970, the year before he set out across the country with a caravan of 50 school buses full of about 200 folks who had wanted to join him in his tour of speaking gigs, but that was the very year I entered the angry sisterhood, and thereafter I dismissed commune life as a new style of drudgery for women. My basic image was of women in long flowered skirts sweating over wood stoves and longhairs lounging around smoking dope.

A few weeks ago I had a chance to check out this image against the real thing when I visited The Farm, but the image itself was no longer real, I’m not sure why…unless it’s that, having experienced the full fury of the sisterhood, it began to seem like anything would look good. As it turns out The Farm felt extremely good.

At the Gatehouse, which is a sort of checkpoint-charlie for anyone who wants to enter, I was treated right off to some of those famous nice warm vibes direct open accepting attention while they put me through to Winnie (they have their own phone system) and showed me by map to the area where she was living. The Gatehouse is an important place which screens people and commands the post, so to speak. The Farm has about 15,000 visitors a year, and the Gatehouse may often seem like an emergency receiving center for the type of visitor wandering in looking for a refuge.

There’s a visitor’s tent on the land, and anybody who feels like they want to stay there beyond that becomes a “soaker,” soaking up the vibes to see if they like it well enough and if the other folks like them. Whoever you are and whatever your business, everybody you pass waves and smiles at you. After a day and a half I felt like Id been there for years.

It you wanted to stay there isn’t any test to pass. You just have to feel as friendly as everybody else and be willing to work and share. The Farm is a huge place and America’s largest working commune: over 1000 people on 1700 acres of Tennessee farmland. Stephen is unabashedly a kind of pastor with a large congregation who provide each other with a number of the basic necessities right on the land: food production and preserving, housing, schools, clinic, ambulance, midwives, and religious services. They have construction crews and electrical crews and all that sort of stuff. There’s a wood shop, a sophisticated press, a print shop, a farm band that plays free gigs, and a soy dairy and canning center where the “ladies” preserve some 25,000 quarts of fruits and vegetables.

The Farm also wants to help feed the world, and presently Stephen is working in Guatemala with a crew of Farmers building houses and schools and setting up clinics in cooperation with the Canadian government, which donates the supplies. Next to food production, possibly the biggest Farm operation is the delivery of babies, although it doesn’t bring in any revenue, which they sorely need to pay off their land debt and for operating expenses, equipment and medical attention beyond their own primary health care. For example, they paid $514,000 recently to have some dude put back together who fell out of a tree.

Many Farmers work off the land to bring in this revenue, and their books are a lucrative source of income. Stephen told me they made a million on their books in the first eight months of sales, and this October they grossed $328,000 on four books. Anyway the delivery of babies is a key agency in this “new world” community. Currently they have six midwives and two apprentices and at this date they’ve delivered close to 500 babies, about half of these from women off the Farm who come there specifically for this service. There are 350 children living on the Farm. The Farm people started delivering babies on the Caravan over five years ago, before they bought the land.

I think Stephen was the first midwife and he taught the women. I asked Mary Louise, one of the midwives Winnie introduced me to at the canning center, how they fare with the local doctors and hospitals and she told me they had no trouble at all because their services are free. It’s money she said that makes the establishment feel competitive. Nonetheless I think it’s the Farm attitude chiefly that keeps them out of trouble. They’re very friendly with all the locals, and occasionally they’ve required the local hospital in an emergency for a difficult birth.

At the same time it is a radical outfit. Here’s what they have to say in the introduction to their book Spiritual Midwifery (published last year on The Farm press): “This is a spiritual book, and at the same time it’s a revolutionary book. It is spiritual because it is concerned with the sacrament of birth passage of a new soul into this plane of existence. The knowledge that each and every childbirth is a spiritual experience has been forgotten by many people of this culture. This book is revolutionary because it is our basic belief that the sacrament of birth belongs to the people and that it should not be usurped by a profit oriented hospital system.” The midwives who have authored this book feel that returning the responsibility for childbirth to midwives rather than a predominantly male medical establishment is a major advance in self-determination for women. The wisdom and compassion a woman can intuitively experience in childbirth can make her a source of healing and understanding for other women.

They also encourage women not to have abortions. “You can come to The Farm and we’ll deliver your baby and take care of it, and if you ever decide you want it back, you can have It.” A book due soon is about natural birth control, called A Cooperative Method. Another book they’re working on will be called How To Raise A Sane Kid. Next to Stephen. the midwives have a lot of authority on The Farm. They’re respected and heard.

The system of authority on The Farm is different from anything we’re accustomed to through elected leadership and bureaucratic hierarchies. All things flow from trust and agreement in a few basic principles: no Individual comes before the welfare of the group; all material goods are held in common. Violence in any form, mental or physical, isn’t tolerated; vegetarianism is practiced and there isn’t any smoking or drinking; fathers participate fully in bringing up the children; and the Christian virtue of the love of ones neighbor is the order of every day.

Everyone then is a counselor, although Stephen is held by the group to be a special repository of wisdom and somebody whose words and actions count as a model of behavior for the others. He does not issue any orders, he just says truths. If you don’t agree you don’t have to stay, Likewise the midwives are considered to have special knowledge, and they’re consulted for marriage counseling, on how to bring up kids, health and sanitation, and any kind of problems.

The governing body, if that’s the proper phrase, consists of a Board of Directors, about 15 people who are the heads of each work crew. The head honcho or main manifestor they call it, from utilities, the wood shop, the midwives, canning and freezing, farming, trucking, etc., comprise the Board of Directors, which really runs the Farm. Stephen is not a member.

It isn’t difficult to discern here the basic outline of tribal organization: the Chief, the religious council, midwives, and the governing or secular council. Although the midwives are not so clearly defined, if My own impressions mean anything, they constitute one part of a tripartite organization. The Board of Directors figure out what they have to have to stay healthy and what the priorities are: what houses get built, what land to buy, what equipment they need. Recently they acquired incubators for their baby operation.

There are other Farms around the country, in California, Wisconsin, Colorado, Florida and New York, all under the spiritual leadership of Stephen, and representatives of these Farms come to Tennessee to meet to coordinate activities like trading and trucking and deciding such things as how valuable it would be to send the band to Vancouver. These Farms are all in radio communication. Ultimately I can envision far flung communities like these united by the best aspects of technology: communication and travel services.

Standards for behavior at the Farm are very rigorous and this includes codes for sexual and marital relationships that we now associate more with the Fords and the Bible Belt than with the new hip Hollywood America of loose free and urban individualism. In Stephen’s book, if you have sex with somebody you’re engaged and if you have a baby you’re married. He discourages sexual license and inspires his flock to go the distance with trying to work it out for life once they take the vows. This is hardly a “free love” community; at the same time there are no rigid rules. Some folks living there are not formally married, and there are quite a few single women with children. The idea expressed in Stephen’s dicta about engagement and marriage is that intimacy is a heavy thing, and you wouldn’t want to enter into it without a sense of commitment and continuity, a sense of regarding the whole of your partner as a proper concern.

The Farm has a strong commitment to raising all the children born under its auspices, thus obviously stable relationships are essential to The Farm’s continuity. I personally like their rationale because its based on real feeling and compassion, and this is the key to the whole Farm operation. All Farm decisions are dictated by compassion. A decision to throw somebody off The Farm is based solely on saving good feelings. Stephen will sometimes tell someone to leave for a month if they’ve been violent. Also occasionally someone will be busted from their job if they’re not cooperative according to the lights of the group or if they cause a malfunction by their carelessness.

Since staying cool is so central to the functioning style at The Farm, I wanted to know what opportunities there are for expressing primal (parental) stuff without being considered unsociable. Stephen told me they don’t mind anybody freaking out so long as they don’t get mean. I had a feeling they have a good way of dealing with symptoms at The Farm. but not necessarily with deep causes and Stephen said you can’t get at causes without cooperation. I couldn’t deduce much from that, but I do know they’re committed to “getting straight” with each other, they’re not patty footing around about how they feel, and in this way presumably they can deal with conflicts and prejudices before they reach the anger stage.

Also Stephen urges Farm folks to maintain or re-establish good family connections to work it out with parents, relatives, the friends back home. By extension, The Farm connects with the society at large. For example, most Farm folks voted in this recent election (for Carter).

After talking to Stephen, I asked Richard (my son) who arrived there not long after my visit how he felt about Stephen, since Richard had the conventional paternal authority figure in his background (“I’m right because I’m your father” sort of thing) and Stephen is clearly an alternate paternal model. Also I’ve been asked how I feel about Stephen in this role since I’ve been so un-authoritarian as a parent is crucial here. I have been authoritative in that I’ve exerted the full weight of my influence by my own example and belief system, and this influence has been beneficial exactly proportionate to my own developing sense of responsibility and vision. I couldn’t expect my kids to be any more than I am, so the idea here is that I become the most I can myself. This is the kind of basic authority each of us exercises. And when I see my kids are being smarter than I am I learn from them.

Stephen has a very evolved sense of his own responsibility, and therefore I trust his authority. As for Richard, he hasn’t communicated with Stephen personally yet, but he knows about the “problem”, the background stuff, and he intends to unblock himself so he can learn things from older dudes — So who is Stephen? He’s 41 years old and the first time I saw him I thought he was Jesus. I’d seen him before in art books. I don’t mean the stern forbidding Jehovah types, nor the sad mawkish El Greco types, nor any of the crucified anguished types. He just looked warm and benevolent in the nordic style.

I’d seen a lot of Jesus hippies around, but Stephen looked authentic somehow, possibly because he seemed so solid and connected and right there. His gig is that he isn’t interested in complaining about the world, he’s setting out to change the world just by doing things differently. He doesn’t think revolutions per se change anything because they’re rooted in violence and the idea that some people are expendable. In his book Caravan, he says, “There isn’t anybody you can kill who could improve my situation. My well-being is not dependent on anybody else’s absence. That’s one of the criteria of a real revolution. It’s got to be based on love and it’s got to be based on truth. It’s got to include everybody from in front.”

Stephen has emerged as perhaps the one indigenous American religious leader with a broad appeal to the new generation of flower people spawned by the 60’s. He was about 32 when the Haight bloomed in ’66 and he was teaching English at San Francisco State College. He had a masters degree and he was going to be a writer. What happened he says is that he was supposed to be telling people where it was at and he didn’t know where it was at yet himself, and his students were leaving school and going off and hanging out on Haight Street and growing their hair out. So he went and did that with them.

“During that time I was taking psychedelics, and I learned about whole new planes of experience that I’d never known the existence of before, that were just as valid as the ones I had known before.” He said he used to teach people things where he had a curriculum or something to teach them, “and any human contact we did was on the side. They said that you were an interesting teacher if you also made human contact while you did the information thing. Well, I found out the information thing was a shuck, and I didn’t want to do it. I would rather do the people thing.”

That’s what I meant about not wanting to send my kids to school. No amount of skill and information seems worth the price our children pay by the loss of their souls in the school system. One of the first things Winnie wrote me from The Farm was “people are real compassionate here on an all the time basis.” I wanted for my kids what I never got myself in any school or other group environment, except what little I could rip-off from favored peers or pet teachers: real affection and compassionate attention.

So then Stephen went back to San Francisco State College and conducted what they called Monday-Night classes, which grew and grew, such that by the time I went to one of these classes myself, in 1970, at the Family Dog auditorium, there were hundreds of folks there. My memory is that there were a few thousand. Even before the hall filled up it had a great glow on. Stephen sat in yoga position on some square platform in a gleaming white turtle neck. He raised a rams horn for the signal to begin and several other horns sounded and set the pitch for a mass .

Then Stephen spoke for a long time without benefit of mike, answering a lot of questions. Sometimes it sounded like a course in comparative religion, except that his lingo wasn’t very professorial. A great basis of his appeal, akin to Rum Dum’s (Ram Dass -rrl), has been his facility for converting thick intellectual stuff into a readily comprehensible vernacular. He speaks the common tongue and makes many concepts that seem esoteric and impossible even to the initiated instantly accessible. I can personally appreciate his use of karma for instance, since I toss the word around a lot but I never saw a definition of it that stuck with me. Karma he says is just how you move through life by the law of cause and effect. Or, as you sow so you shall reap. Thus can make you feel more responsible for your own actions right away.

In this sense Stephen is a preacher. He never conceptualizes for the hell of it; his exploration of a concept is attached in the here and now, to your own behavior and attitudes, Toward this end also he plays the bead game for the greater good. The bead game is a method of transposing the terminology of different disciplines to show how all the belief systems are grounded in the One. If you hear all, this it’s impossible to suspect that Jesus or Buddha or any other god is superior to any other one.

Yet the female deities are not exactly interchangeable with their male counterparts. I went to the Sunday morning meditation in the meadow while I was visiting there in Tennessee and I couldn’t help thinking this time around that Stephen has the profound confidence and credibility that only a man in our society can generate to lead. While women may be moving into the political ranks of our appointed and elected authorities in the hierarchies of government, I have yet to see any women in our part of the world command the kind of attention it takes to sustain a community that runs as a group head.

A candidate for this high sort of (unadorned) power first generates confidence through their own naked presence and ability to articulate the common knowledge. Gradually an accretion of individuals entrusts such a person with their collected energy, which they receive back in the form of a focused articulation. This is what the “chief” does. Should the chief fail to reflect the interests and devotion of the group, in any way setting himself apart from or above the group, the group will withdraw its energy from this chosen receptacle.

Stephen says, “I have no money, no salary, no ace in the hole, I don’t own anything,” and yet Stephen comes with the credibility of his sex, which is defined as credible in our society by the very tradition he deplores: private ownership and the profit motive. For this and other reasons I have mixed feelings when I see Stephen doing his stuff. At the meditation that Sunday he married about six couples– a simple beautiful ceremony that takes a couple of minutes apiece – and I asked him afterwards if he ever said “I now pronounce you woman and husband” and he replied that he did sometimes alter the words of different rituals. I confess that I didn’t believe he ever altered the words of this one in particular, but I decided presumptuously that if he never has before he will in the future, in which case he would be performing a feminist act, for embedded in the ritual words is the clear patriarchal meaning they carry.

I also decided I asked him the question as a defense against the real emotion I felt while he was marrying everybody. I told Winnie if she ever got married I’d need a boat to get out of the place. I continued feeling defensive after we wandered back through the woods to the tent structure where Winnie was living with Linda and Kenneth and their three babies Abel, Emily and Ruth. Linda disapproved of my turkey-baster idea for a woman to have a baby without benefit of intercourse, saying it wasn’t fair to deprive the father of the pleasure of helping bring up the kids; and since she was still skeptical when I said naturally it would only be by agreement, I added well – we have different strokes for different folks. I said I wouldn’t want to exclude males from my own community but I wouldn’t want them to dominate either.

The Farm is still not my own kind of place, nor do I know what (that) is exactly except what I’m familiar with, which is the lonely retreat of a writer, but I have no doubt that The Farm is inherently correct. I don’t know why any woman wouldn’t want to go there, unless as a woman you don’t want to be around that many males or around so many babies and so many women who have babies and who like to do traditional woman things. My daughter enjoys the babies there, but she’s been working in the wood shop and she’s going to start construction work on the high school soon.

I suspect the Farm may be harder on the men than on the women because they have so much more to give up in a sense: their pursuit of individual importance. The women who followed Stephen never entered the ego-stream of America’s “liberated” women. If they’re going to assert themselves it will be in a wholly different context (i.e., the midwives), and it seems a lot healthier to me for a start, being rooted in cooperation rather than competition.

Marxist intellectuals take note and beware: your dreams may be coming true. These communities are making good the promise of Freak America to build a new society based on love and socialism. Freak America is not over – it’s just become serious and functional. Stephen led a whole bunch of them out of Egypt into Tennessee, saying “I feel like beatniks have been spaced long enough, and that we know where it’s at, and that it’s time we got off welfare, gave up food stamps, and began to produce with this energy which we say we have so much of. They don’t deny that we have a lot of juice. They just think it’s a little strange to see people taking baths in energy while there’s other people dying for, lack of it.”

Over a long enough period of time, the gradual accretion of these “alternate” communities will simply displace the dominant mode of capitalism, which is crumbling slowly of its own internal accord. Nobody needs to overthrow capitalism. It will die a natural death. In the meantime it’s very exciting to be living in a time and a country where new viable wholesome tribalistic structures are emerging right in the shadow of the collapsible monster. If I can’t quite make it there myself, I’m happy to be a part of It through my kids, who may not stay, but who will have stayed long enough to make the irrevocable contrast.